Daniela Cotimbo

Art Curator

- Home

- About

- Re:Humanism

- Exhibitions

- OVERTON WINDOW: Solo

- Muovendomi, stando ferma.

- Second Order Reality

- The Stone Monkey

- Tecnoriti

- Sparks and Frictions Re:humanism #3

- Beyond Binaries

- Distrust Everything

- IperSitu

- Non sono io il fotografo

- Object Oriented Choreography

- Don’t you forget about me

- Re:define the boundaries Re:humanism #2

- Within a latent space

- Allegra ma non troppo

- Complessità

- Re:humanism art prize #1

- Ionian Archaeological Archives

- Die andere Seite

- Models of display

- Se non vedete segni o prodigi non credete affatto

- CsO

- ANDIAMO Là

- Talk

- Publications

- News

- Contact

Don’t You Forget About Me

Don’t You Forget About Me

5-15.07.2021

Numero Cromatico

Curated by Daniela Cotimbo

in collaboration with Re:Humanism

With the participation of Franco “Bifo” Berardi

Sala Santa Rita, Roma

Don’t You Forget About Me is the result of a previous collaboration with collective and research centre Nume- ro Cromatico during the second edition of Re:Humanism Art Prize. On the occasion of the exhibition held at MAXXI – Museo delle arti del XXI secolo di Roma in May 2021, the collective presented Epitaphs for the Human Artist. The installation project consisted of three hand-sewn, multi-coloured banners and a lectern holding a book – a collection of epitaphs generated by an Artificial Intelligence they had trained for such purpose. Shortly afterwards, the desire to design a project for Sala Santa Rita led us to renew this collaboration with Don’t You Forget About Me, which holds in itself some elements of the previous project — namely Artificial Intelligence, epitaphs, banners — yet charged with new levels of interpretation starting from the context it was conceived for, from both an architectural and religious perspective. Not by chance, opting for liturgical devices as potential aesthetic renderings is something that Numero Cro- matico had already tried out in Epitaphs, almost providing some sort of set for the book itself. Epitaphs are literary works that originate from the contexts and traditions of popular culture, though here they stem from a technological procedure.

Indeed, as the artists state, the epitaph was born in the classical era as a commemorative speech performed by an orator in honour of war heroes. In modern poetry it has increasingly- ly acquired the shape of a short text used as a sepulchral description, thus becoming an actual literary form employed not only by those who knew and loved the deceased but also by artists, intellectuals and poets. The project fits perfectly into the re-research methods of the collective, which has long been interested in using the means of popular culture – stadium banners, social networks, advertising tarps – proposed as artistic devices capable of both conveying their aesthetics as well as altering the way the artwork is perceived. The study of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is another piece to add to this broad research. AI is among the most state-of-the-art technologies currently at our disposal. It can learn from a given collection of data and generate its own results based on the analysed patterns. Nowadays such technology plays a pivotal role: as a matter of fact, algorithms tell us what to watch, what to buy and the people we should go out with. These sophisticated mechanisms are capable of writing articles, screenplays for both TV and video games, music pieces and producing brand-new images.

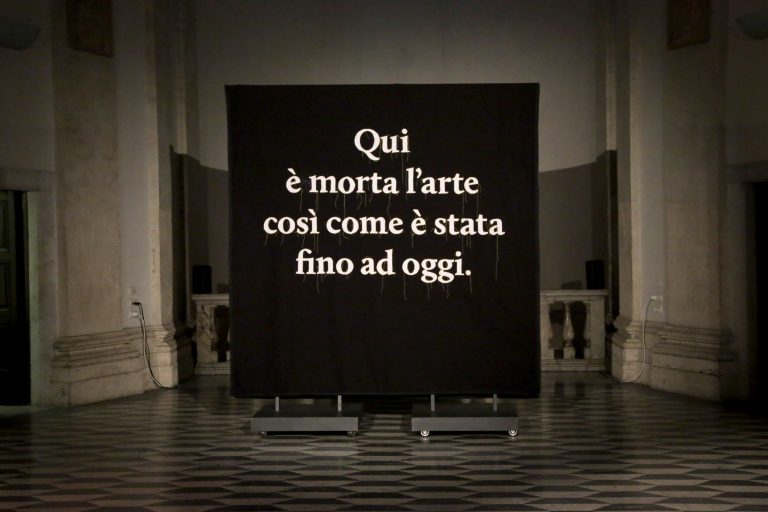

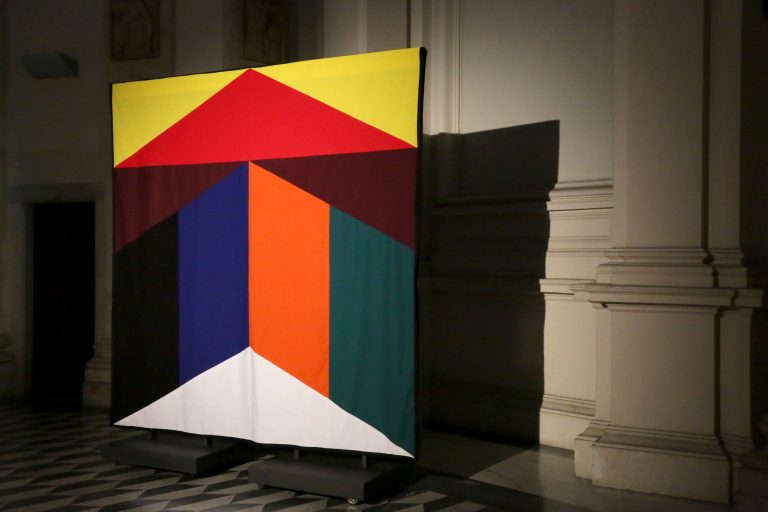

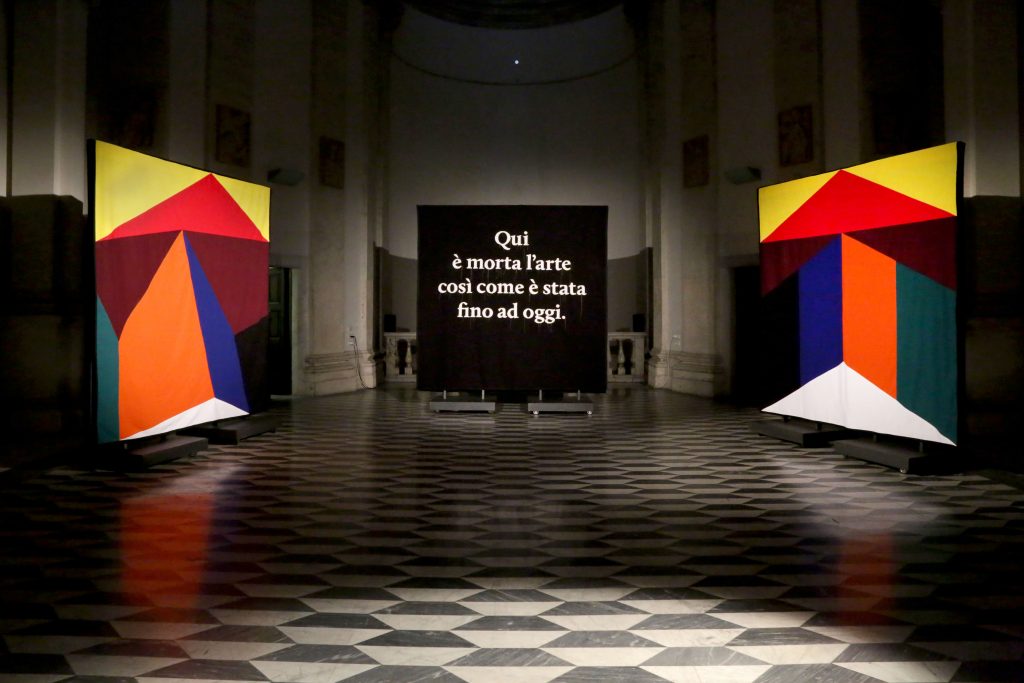

Numero Cromatico exploits this technology and its pervasiveness so as to grant the public an experience that draws from the artist’s expressive abstinence. The AI-generated texts are thus indistinguishable from those written by a human author. However, taking a closer look at those compositions that result from technological procedures will bring out their enigmatic nature, rather puzzling to be entirely caught. This sense of estrangement is sharply intensified by the voice of philosopher Franco “Bifo” Berardi, who acts out a real homily by reading a selection of the epitaphs delivered to the public through widespread audio. In line with the collective’s research on the relationship between art and neuroscience and the design of experiments in neuroaesthetics, the employment of AI allows for the investigation into the machine’s generating potential as well as its effects on the way the public perceives an artwork. Hence, the exhibition designed for Sala Santa Rita proceeds by subtraction and overturns in meaning. The space embracing the project is not – or at least is no longer – a sacred space. What remains of its sacred origin are the architecture and a certain solemnity, yet it has lost its furniture, function and its actual orientation (having been dismembered in 1928 and then pieced back together in 1940 according to a new trajectory). Also, the constitutive parts of the artwork become non-being – beginning with the three hand-sewn banners which simulate in size the large altarpieces normally found in religious architecture, yet renouncing the principle of representation in favour of geometric and textual forms. The two lateral banners directing the spectator towards the centre show primary-coloured geometries that mirror one another according to an apparently random logic. At a deep- er analysis, one realises how the two different configurations conceal a common origin to which algorithmic computation attributed two separate identities. The reference to the tradition of oriental iconography, as well as to alchem- ical and kabbalistic theories and to all forms of representation of the Sacred through mathematical order, is rather strong, even more so if viewed within the exhibition context. In a recently translated essay, philosopher Matteo Pasquinelli when looking into the origins of the relationship be- between human beings and algorithms – which today sets the basis for the development of technologies such as AI – traces it back to Shulba Sutras, Indian literary forms dating back to 800 b.C., yet recalling even more ancient rituals. The Agnicayana ritual, for example, involved the construction of complex altars to be conceived on the basis of geometric shapes borrowed from algorithmic calculus. In the essay, Pasquinelli demonstrates how this inclination towards the mathematical organisation and rigour is not an aberration of contemporary society, but rather it is a social necessity inherent to human beings on which, however, we have lost the habit of critical practice. With no intention of delving into what is a very rich tradition that brings spirituality back to the search for a higher order based on mathematical principles, particularly noteworthy is how Numero Cromatico draws such forms of meaningful production from their context so as to bring them back to the spectators, in a mimetic way, who now find themselves in a different space, whose conditions have changed. While approaching the centre of the exhibition space the public realises that this third banner renounces chromatic and geometric forms in favour of textual ones: Here died art as it was made up to this day. The choice of the epitaph is, once again, not left to chance. Instead, it recalls a new condition of negation, that of art – Here died art – and that of the present time that escapes at the very moment in which we take note of this caesura – as it was made. Art, however, is there, it is right there in front of our eyes and the third part of the sentence “up to this day” reminds us that what we are witnessing is the ongoing possibility of a new art. The collective thus manages to come up with an aesthetic device capable of questioning those interpretative tools leading to the experience of the public. It does so by emphasising the relativity of both the gaze and the present time. Memory – evoked by the title of the project itself – stands for the essential condition of rootedness on which to establish the encounter with the new. The audience is called to read through the plots of their own sensitivity, to question time as an absolute moment, by probing the potentialities and lim- its of subjectivism, filling that void of meaning that the authorial dimension deliberately leaves uncovered.